Quel presepe di tante piccole capanne. Il Natale del 1944.

Testo di Vincenzo Battista.

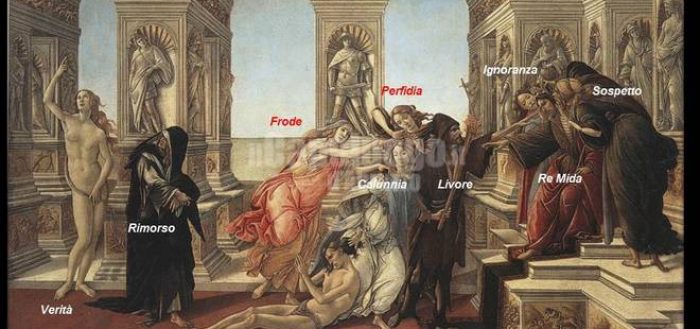

L’incenso dal profumo sottile, balsamico, caldo, legnoso, invadente, fumo fragrante, nuvola aromatica, proveniva dai rilievi montagnosi che declinano lungo le coste del Mar Rosso; aveva il potere di addolcire le amarezze, come vuole il rito, trasformare il dolore e le pene nella sostenibilità dell’essere; l’incenso, quello prescritto a Mosè per i profumi e utilizzato anche dagli antichi Greci e dagli Egizi, nei loro templi, che trasudavano di questo odore dolce offerto in vari modi: una liturgia senza tempo.

Poi la mirra, con il compito di coprire l’odore della morte, profumo resinoso e balsamico per attenuare la passione, dalle più diverse qualità, acre, caldo, assicurava l’imputrescibilità dei corpi, qualcosa d’infinito, come l’anima; gocciolava in primavera dai buchi delle cortecce usata per le mummificazioni e per le imbalsamazioni. Resine del paradiso quindi, balsami pregiati, aromatici, trascendenti il dolore, la morte, celebravano il trionfo del non essere. E infine l’oro che simboleggiava la regalità, il primo metallo conosciuto dall’uomo fin dai tempi preistorici.

Tutto questo portavano con loro i magi, sacerdoti di una casta religiosa e primitiva, ma secondo le fonti tardo greche anche astrologi, indovini e fattucchieri. Giunti nella pianura, racconta una storia, che potrebbe essere una fiaba di Natale ambientata in un cielo pieno di astri, dall’aria gelida, e dal terreno coperto di neve come mai non si ricordava, i Magi si muovevano a fatica, simboli della divenuta immortalità con le loro resine, ma soprattutto di quella solidarietà che non stabilisce mai i confini; e passarono anche qui portandosi dietro una grande umanità, costituita da contadini, pastori, falegnami, fabbri, boscaioli, maniscalchi e tanti altri ancora in quel tremendo inverno del 1944.

Queste persone erano spinte da un’antica legge di fratellanza, aiuto, compassione verso quei “poveri Cristi”, dentro quelle piccole capanne, di quel grande presepe, che era diventata la Valle Peligna, in un particolare Natale del 1944. ” In molte capanne delle campagne di Corfinio, nascosti, ci vivevano gli inglesi, fuggitivi, impauriti, gelati, disperati – raccontano – .

Mio nonno e mio padre preparavano un cesto con dentro pane, formaggio, una minestra, un po’ di vino e verdura e la portavano di nascosto, senza farsi vedere, in campagna, nelle capanne usate d’estate dai contadini per rimettere gli attrezzi agricoli, che erano in legno, con una lamiera sopra. Si parlavano a gesti. Un giovane piangeva mi ricordo, per quella fratellanza dimostrata”. Intorno e dentro i borghi del presepe della Valle Peligna i tedeschi, l’occupazione, i fascisti, i cannoneggiamenti continui, miseria, terrore e poche certezze.

“I contadini portavano gli stivali per irrigare – continuano – e li usavano per farsi strada nella neve. Agli inglesi davamo coperte e cappotti vecchi, la paglia, qualcuno preparava un sacco e dentro ci metteva le foglie di granturco, per farne un pagliericcio. Centinaia e centinaia di uomini li hanno aiutati, e non solo a Corfinio. Con tanti sacrifici molti inglesi li abbiamo salvati”. Di tanti non si è saputo più niente, molti non ce l’hanno fatta, ma qualcuno è tornato per rivedere quelle capanne, quei luoghi, per ritrovare quelle persone e continuare a raccontarla questa storia che assomiglia ad una fiaba di Natale, difficile da dimenticare.

Traduzione : Piera Badia

The incense with its thin, balsamic, warm, wood-scented, pervasive, fragrant smoke, like an aromatic cloud, came from the mountain tops gently sloping down to the Red Sea coasts; it had the power to sweeten bitterness, as the ritual says, to transform pain and sorrows into bearable moments; incense, which was prescribed to Moses for perfumes and used also by the ancient Greeks and Egyptians in their temples, which emanated this sweet smell offered in several ways – a timeless liturgy. Then myrrh, that was used to cover the death smell, a resinous and balsamic scent used to soothe passion, with its many different qualities, acrid and warm, assured that bodies would not rot, something infinite, like the soul; in spring it dripped from the holes of the tree barks used for mummifying and embalming. These heaven’s resins, valuable, aromatic balsams, transcended pain and death, celebrating the triumph of being no more. And finally gold that symbolized royalty, the first metal known by man since prehistoric times.

All this carried along the magi, priests of a chaste primitive religion, but according late Greek sources also astrologers, fortune tellers and magicians. Once they came to the plain, tells a story that might also be a Christmas tale set against a starry sky, in the freezing air, and on a snowy land as never before, the Magi were moving slowly, symbols of immortality with their resins, but above all of that solidarity that will never define borders; and they walked here too, carrying along a great crowd of peasants, shepherds, carpenters, blacksmiths, woodcutters, farriers and many others in that terrible winter of 1944.

These people were driven by an ancient brotherhood law, aid, compassion towards those “poor Christs”, within those small huts, in that great manger which was by then the Peligna valley, on one special Christmas in 1944, “Hidden in many huts in the Corfinio countryside, lived the fugitive British, frightened, freezing, despairing – so goes the story.

My grandfather and my father would prepare a basket with bread, cheese, some soup, a little wine and vegetables and carried it secretly, being careful not to be seen, into the fields, to the huts used in the summer by peasants to store their tools, wooden huts with tin roofs. They spoke with gestures. A young man was crying, I remember, for that brotherhood token”. Around and within the villages of the Peligna manger were the Germans, the occupation, the Fascists, never-ending bombings, misery, terror and few certainties.

“The peasants used to wear their watering boots – he goes on – and they used them to open their way in the snow. To the English they gave blankets and old coats, straw, someone prepared a sack and filled it with corn leaves, in order to make a straw mattress. Hundreds and hundreds of people helped them, and not only in Corfinio. With great sacrifice they saved many English lives “. Of many nothing more was heard, they possibly did not make it, but someone came back to see again those huts, those places, to find those people and continue to tell this story so much like a Christmas tale, a tale that is difficult to forget.

Referenze fotografiche:

Youtube,Ventolargo, Youdoc, il faro24.it, la Stampa, Terre Marsicane, Il Capoluogo.it, L’Abruzzo è servito, 100casa