Raccontare il paesaggio degli uomini: una storia in “ Bianco e nero…”. (Tradotto in inglese).

Testo e fotografia di Vincenzo Battista.

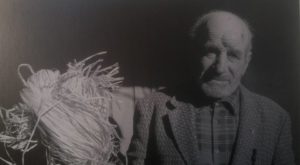

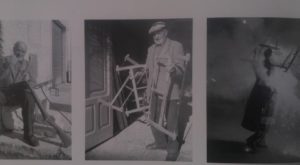

Angelo Santilli nasce il 14 ottobre 1911 a Castelvecchio Subequo ( Aq), figlio di Elia Santilli e Caterina Salutari, che lavoravano come commercianti. A 14 anni iniziò a lavorare nella segheria a Molina Aterno, e due anni dopo fu apprendista nella bottega di Mastro Genuino, Castelvecchio Subequo. Poi lavorò come raccoglitore di erbe medicinali, puparo, luparo, pescatore, taglialegna, fabbricante di fuochi d’artificio, falegname, guaritore con le erbe locali del Sirente. Emigrato in Africa nel 1936, fu operaio militare in un’officina meccanica, e tornò in Italia nel 1938. Subito dopo la Seconda Guerra Mondiale lavorò nella costruzione di tunnel a Roma per un anno. Viaggiò sui treni in carri bestiame per scortare le spedizioni di farina e patate. Nel 1951 si trasferì in Australia dove lavorò per 18 mesi come falegname costruendo case di legno. Ritornato dall’Australia, riprese il lavoro di falegname alla segheria.

“Quando ero giovane – ha inizio il suo racconto – andavo alla macchia, al Guado dell’Orso (Monte Urano) a fare la legna. Avevo allora dodici anni; sono nato a Castelvecchio Subequo, nel 1911. Andavo a raccogliere le ghiande sotto le querce, se le mangiavano i maiali. C’erano le stradelle, le mulattiere. Ora si sono ricoperte perché non si taglia più l’erba dei sentieri. Invece nei boschi del Sirente non si andava perché si recavano solo i residenti di Gagliano; prendevi solo la legna secca. Facevi un biglietto ai contrattori che avevano preso il bosco per l’assegna civica: la legna piccola la usavano i carbonai e l’altra la potevi prendere pagando un contrattore. Facevi una salma per l’asino e la notte viaggiavi per portarla a destinazione. Quando andavamo a fare le ceppe partivamo la notte e il giorno dopo stavamo a Castelvecchio, a mezzogiorno. Quella legna era per la famiglia, per l’uso domestico.

Si zappava la terra come gli schiavi. Si metteva il granoturco, la terra non era la nostra. Noi tenevamo le vacche, i cavalli; ma le famiglie più povere dovevano zappare la terra con il bidente per mettere solo il granoturco. La metà al proprietario e l’altra al contadino. L’anno dopo, quando si mieteva, il grano se lo prendeva il padrone. Nel mese di agosto appena mietuto, si ricominciava a rompere la terra col bidente, a “stoppare”. C’era miseria forte. Da Secinaro mandavano le donne con la legna e l’asino a vendere quattro fascine. Gli uomini andavano a zappare. Le terre erano di Valerio, Don Ciccio, Pirro. In Australia sono stato due anni e mezzo; sono partito quando avevo 49 anni.

Sono stato anche in Africa come operaio militarizzato nel 1936. Ho fatto anche la guerra. I contadini andavano “a giornata”, a zappare la vigna, a sarchiare. Erano famiglie povere. Si andava a prendere un quarto di carne e si “segnava” al quaderno del negoziante. Quando si poteva chiamare la manodopera per mietere, i macellai prendevano i contadini a scontare le giornate, cioè il debito che avevano fatto. La carne si prendeva per un’invernata, poi si chiamava il contadino a zappare; si cercava di fargli scontare il debito. Chi aveva le pecore se la passava meglio. C’era uno che aveva molti figli; noi gli affidavamo la morra e mio padre gli pagava la giornata. Erano poveri non avevano casa, dormivano in una grotta. Nel 1915, dopo il terremoto, furono costruite le baracche perché i centri storici erano stati distrutti e in una stanza ci vivevano anche sette persone.

Due giorni prima di iniziare un lavoro, si andava in piazza, si trovavano gli uomini per lavorare in campagna a giornata, a sarchiare il granturco e le patate. In buona parte si seminavano il granturco e patate. Il granturco si coltivava più del grano perché non avevi molta terra. I campi erano dei padroni e allora si metteva il granturco che andava sempre diviso con il proprietario. Il grano, i padroni lo producevano per loro, sui propri terreni. I contadini coltivavano il grano solo per i proprietari, non potevano fare a metà come invece per il granturco. Con il granturco si faceva la polenta, il “parrozzo”, che ha il sapore di quando “crepa la terra nel mese di agosto”. Quello si mangiavano i contadini. Poi si faceva la pizza, sempre di granoturco, sotto il coppo del camino. Si usavano le piante del granturco per cuocere le patate e la gente andava a raccogliere i “torzi” per il fuoco del camino. Di fuoco ce ne stava poco.

Se i proprietari che ti avevano affittato le terre ti compravano le pecore “alla porta”, quando si tosavano gli dovevi vendere gli agnelli. Se pioveva i proprietari ti impedivano di andare nei terreni perché si rovinavano, “si ammalava la terra”; ti facevano fare i servizi precisi come gli schiavi. La terra si ammalava. Quando la terra è secca e fa un acquazzone, se tu vai a zappare, la terra fa i “chetigli”, cioè si “sgarra”, escono i “restupponni”; quando è così nemmeno le pecore possono andarci. Si chiama “la verde e secca”, la terra si attacca alle scarpe, quella sotto è secca”.

Testo in inglese di Piera Badia

Angelo Santilli was born on 14 October 1911 in Castelvecchio Subequo ( Aq) son of Elia Santilli and Caterina Salutari, who worked as merchants. At 14 he started work in the sawmill at Molina Aterno, and two years later he was an apprentice in the workshop of Mastro Genuino, Castelvecchio Subequo. Then he was a collector of medicinal herbs, a puparo, luparo, fisherman, woodcutter, fireworks maker, carpenter, healer with local herbs from Sirente. Emigrated to Africa in 1936, he was a military worker in a mechanic shop, and came back to Italy in 1938. Soon after WW2 he worked in tunnel constructions in Rome for a year. He travelled on trains in the animal waggons to escort shipments of flour and potatoes. In 1951 he moved to Australia where he worked for 18 months as a carpenter building wooden homes. Back from Australia, he took up his carpenter job in the sawmill.

“When i was young, I went into the forest, at Guado dell’Orso (Monte Urano) to make firewood. I was twelve at the time; I was born in Castelvecchio Subequo, in 1911. I picked up ghiande below oaktrees, pigs ate them. There were small roads, the “mulattiere”. Now they are covered, since grass is not cut from the paths. We did not go into the Sirente woods, because only the residents of Gagliano could go there; we only took dry wood. We paid a ticket to the contractors who had received the forest from the municipality: the small wood was used by charcoal makers while you could take the bigger wood paying a contractor. You prepared a load for the donkey, and travelled by night to take the load to destination. When we went to make the wood we left in the night and the following day we were in Castelvecchio, at midday. That was the wood for the family, to be used in the home.

We worked in the fields like slaves. We sowed corn, the land was not ours. We had cows and horses, but the poorest families had to work the fields with spades to sow the corn. Half to the landowner, half to the peasant. The next year, at the harvest, the landowner took instead all the wheat. In August soon after the harvest the fields had to be cleaned, and work started again. Poverty was great. From Secinaro we sent the women with the donkeys to sell some wood. Men went to work in the fields. The lands belonged to Valerio, Don Ciccio, Pirro. In Australia I was for two years and a half; I left when I was 49.

I also was in Africa as a military worker in 1936. I also fought in the war. The farmers went to work in the fields with day’s wages, to work in the vineyards, to clean the corn. Families were poor. They bought a quarter meat and had it “noted” in the shopkeeper’s book. When labour was necessary for the wheat harvest, the butcher took the peasants so that they paid with their day’s work the debt accumulated. Meat was taken throughout the winter, then the peasant was called to work in the fields to pay for his debt. Who had sheep was better off. There was one who had many children; we gave him some work and my father paid his day. They had so poor they did not have a house, they slept in a cave. In 1915, after the earthquake, barracks were built because the town were destroyed and in one room even seven people slept.

Two days before a work was due, you went to the square, and found the men that would come to the fields to clean the corn and the potatoes.Mostly we sowed corn and potatoes. Corn more than wheat, because you had little land. The fields were of the landlords, so you sowed corn that was always shared with the landlord. Wheat instead was produced by the landowners on their own fields for themselves. Peasants cultivated wheat only for the landowners, the harvest was not split as for corn. With corn you made polenta, the “parrozzo”, with that taste of the soil breaking in august. That was the peasants’ food.

Then you made pizza, always with corn, under the fireplace cover. Corn leaves were used to bake the potatoes and corn plant cuttings were used to make the fire. There was little fire. If the landowners who had given their land in rental to you bought you sheep to take to the fields, when the wool was made you had to sell them the lambs. If it rained, you were forbidden to go to the fields, not to ruin them, “the soil got sick”; so they asked you to do other things just like slaves. The soil got sick. When the land is dry and a shower comes, if you go to work the fields, the soil makes “chetigli”, that is, it is”disrupted”, the “restupponni” come out, and not even the sheep can go there. You call it “green and dry”, the soil sticks to the shoes, and the soil underneath is dry”.