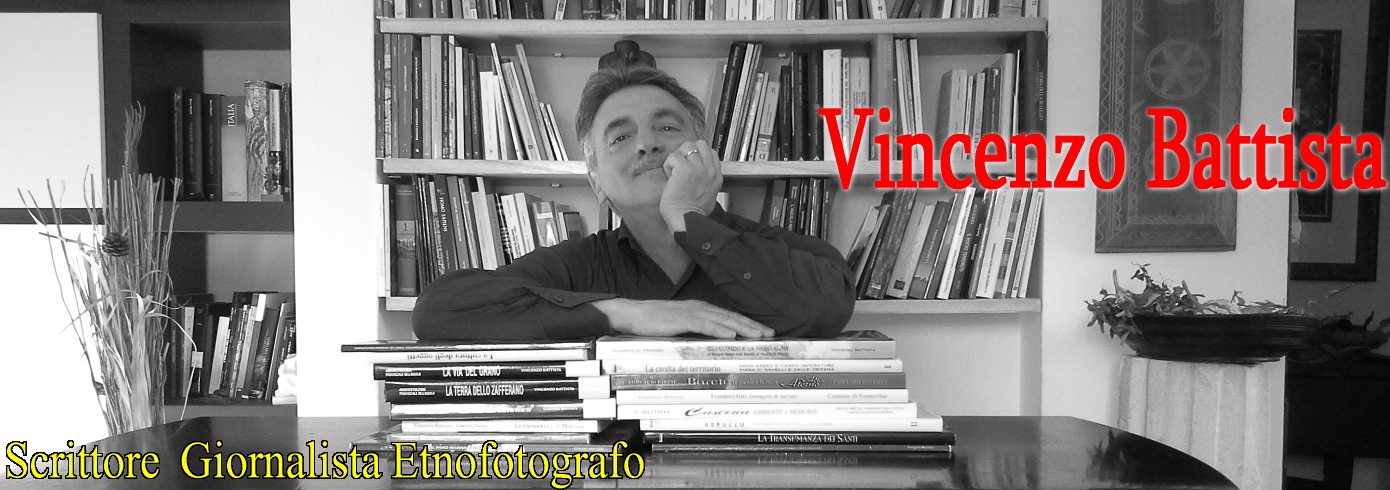

Testo e fotografia di Vincenzo Battista.

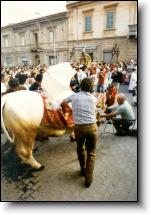

Il giorno della Pentecoste, a Loreto Aprutino, in provincia di Pescara, ha inizio la festa popolare che vede la sfilata nelle vie del paese di un bue sormontato da una bambina con una particolare fisionomia e con in bocca un garofano rosso. Dalle prime luci dell’alba, in una contrada di Loreto Aprutino, inizia la “Vestizione” e la preparazione del bue, oggi non più usato nei lavoro della campagna ma un tempo necessario per le attività agricole e il lavoro contadino. La “Vestizione” è lunga, accurata, meticolosa da parte del comitato e del proprietario del bue che custodisce l’animale divenuto simbolo insostituibile dell’intera comunità religiosa. Ghirlande, copricorno di raso scarlatto, il corno rosso, campane d’argento, stoffe pregiate, specchi ed altri simboli come l’effigie di San Zopito rivestono e arricchiscono il bue che per un giorno, in un anno, viene spostato da una ordinarietà quotidiana per divenire il “tramite”: elemento soprannaturale, di devozione, di rispetto, e capiremo il perché. La preparazione delle ghirlande e dei nastri sulla testa del bue di Loreto Aprutino occupa molto tempo prima della sfilata. La leggenda narra che alcuni contadini erano impegnati ad arare con un bue un terreno in località “Collattuccio” nel giorno di Pentecoste, irriverenti della festività e della processione di San Zopito che attraversava l’abitato, le campagne e giungeva davanti al loro campo. Al passaggio della statua del santo, il bue che trainava l’aratro si inginocchiò davanti allo stupore dei contadini e dei fedeli al seguito della processione. Fu un evento soprannaturale. La sfilata della statua di San Zopito adesso può avere inizio. La leggenda, continuando nel suo racconto mitico, vuole evidenziare che nel giorno dedicato alla festività gli uomini non devono dimenticarsi dell’autorità religiosa, San Zopito, protettore del paese, e sono richiamati al rispetto del passato, l’accadimento prodigioso epico dell’animale, il bue, che si inginocchia al loro posto… Un altro elemento della narrazione leggendaria è costituito dalla bambina che, a cavalcioni sul bue, sfila per tutto il percorso della rappresentazione popolare. La bambina con l’abito bianco e ricami dorati, coperta di monili d’oro, secondo la leggenda del bue e del santo, è l’angelo messaggero che San Zopito ha voluto inviare: il tramite cioè tra la divinità e i contadini che, collocato sulla groppa del bue con in bocca un garofano rosso sbocciato straordinariamente nella stagione primaverile, “guida” il bue e lo fa inginocchiare. Il tracciato del corteo processionale prevede la sosta e il rinnovato rito dell’inginocchiamento del bue che si ripete davanti al mulino, ai palazzi del potere locale, alla banca, il castello, il frantoio e davanti alla chiesa. Luoghi che si sono sostituiti all’originale culto popolare che prevedeva l’ingresso in chiesa, l’inginocchiamento del bue e il suo defecare davanti all’altare, che era allora considerato un presagio favorevole da parte della società contadina per l’imminente stagione agricola dei raccolti. Forse questo rituale che profanava il luogo di culto può essere letto come una forma di riscatto da parte della cultura contadina che espropriava il tempio religioso dei suoi significati con una azione che rimarcava, e comunque veniva tollerata, dalle autorità religiose, ma che tuttavia voleva sancire il predominio, per una volta l’anno, di una società rurale schiacciata da imposte e gabelle che magari provenivano anche dalle proprietà del latifondo ecclesiastiche. In seguito questa pratica è stata abolita per l’intervento della Chiesa.

Traduzione Piera Badia

On Pentecost day in Loreto Aprutino, Province of Pescara, there takes place a folk festival with a parade through the alleys of the town of an ox, ridden by a little girl chosen for her appearance and holding a white carnation in her mouth. From the early morning hours in a countryside quarter of Loreto Aprutino the “dressing” and preparation of the ox begins; nowadays the animal is no more used in agricultural work, but was once necessary to man’s farming work and activities.

The long, careful, detailed “dressing” is performed by the feast committee and the owner who looks after the animal, an essential symbol of the whole religious community. Wreaths, horn covers in scarlet silk, silver bells, precious cloths, mirrors and other symbols like the picture od St. Zopitus, cover and embellish the ox, who will become, for one day a year, not the animal of the everyday work but the “vehicle”: a supernatural element of devotion and respect, and here is why.

The preparation of the wreaths and ribbons on the head of the ox in Loreto Aprutino.

The legend tells that some peasants were tilling the land with the help of an ox in a district called “Collattuccio” on Pentecost day, forgetting the respect due to the festivity and the procession in honor of St. Zopitus, that had left the town and crossing the fields was just then passing by their field. When the saint’s statue was passing by, the ox that was drawing the plough suddenly knelt down, to the awe od the peasants and the faithful following the procession.

The procession of the statue of St. Zopitus.

The legend had the function to teach that on the day devoted to a religious feast men should not forget the religious authority, namely St. Zopitus, the patron of the place, and are called back to the due observance by the miraculous behavior of the ox, kneeling down as they ought to have done.

Another element in the legendary tale is the little girl riding the ox throughout the procession itinerary. The girl wears a gold-embroidered white dress and is covered in gold ornaments; according to the legend of the ox and the saint she is the messenger angel sent by St. Zopitus: the “intermediary” between God and the peasants, who, placed on the back of the ox, and with the red carnation blossoming exceptionally in spring, “rides” the ox and makes it kneel down.

The itinerary followed by the procession includes a number of stops, where the kneeling rite is repeated, before the mill, the palaces of the rich people, the bank, the castle, the oil mill and the church, a tradition which took the place of the original folk procession, when the ox was only led into the church, and made kneel before the altar. In case the animal dropped stools just at that moment, that was held by the peasants as a very favorable omen for the coming harvest season.

Possibly this ancient rite, which was actually a profanation of the church was a kind of revenge of peasants’ culture, expropriating the religious building of its meanings with an action that however had a religious aspect and was allowed by the church authorities. The symbolic gesture, once in a year, was a sign of the supremacy of the rural culture usually crushed by taxes, levied also by the proprietors of the church lands. The custom of the ox entering the church and dropping was later abolished.